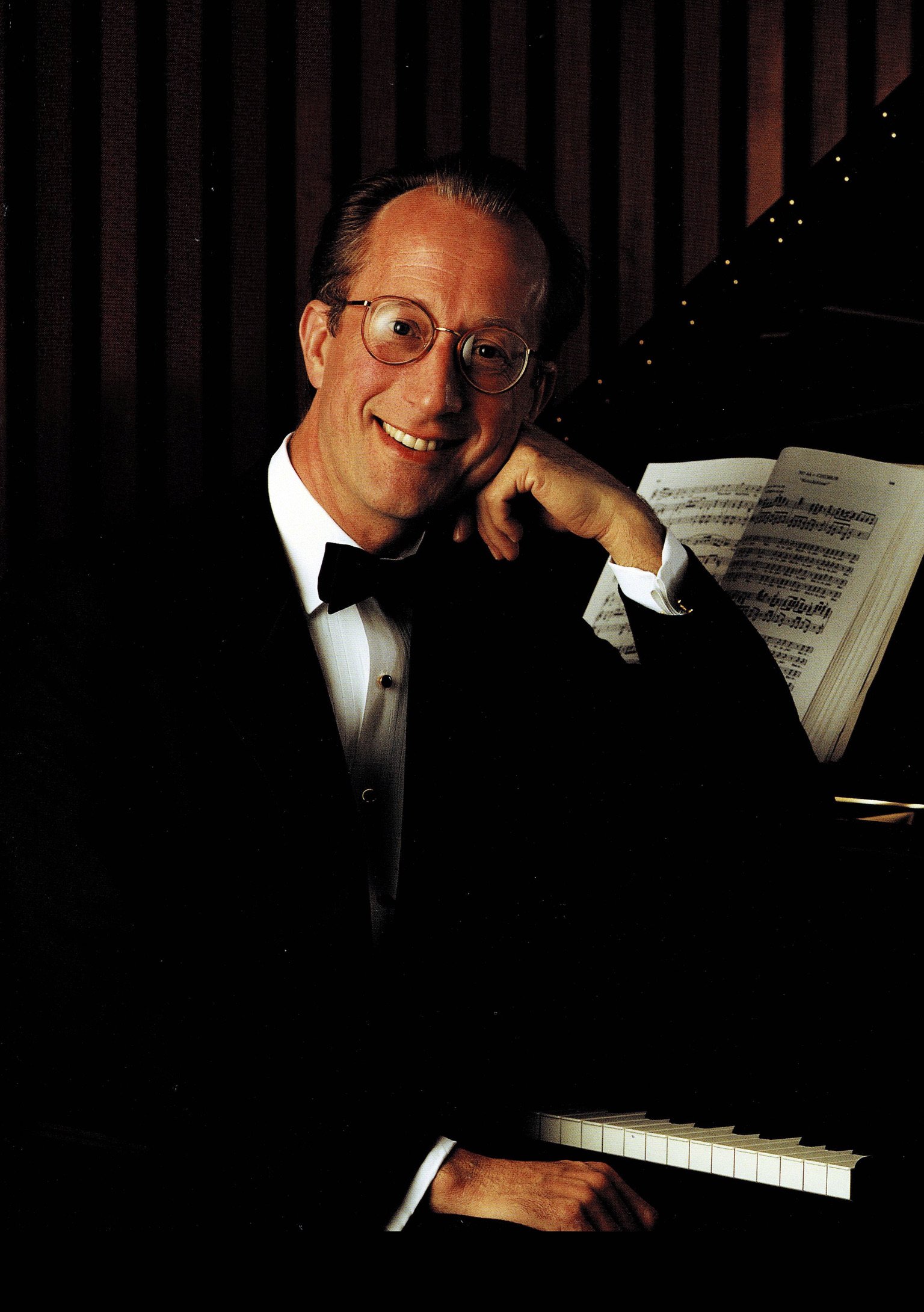

LOU MAGOR SCHOLARSHIP FUND

“Music is one of those things that, thank God, can’t be described in words. Without it I’m lost. With it I’m happy. I guess what it means to my life is that it is my life.”

—Lou Magor

The Lou Magor Scholarship Fund supports the educational programs of the Institute for Creativity. Our vision is to ultimately create an endowment that removes the financial barrier for individuals to access arts education here at Common Tone Arts.

MORE ABOUT LOU’S LIFE

BY PETER MINTUN, NEW YORK CITY

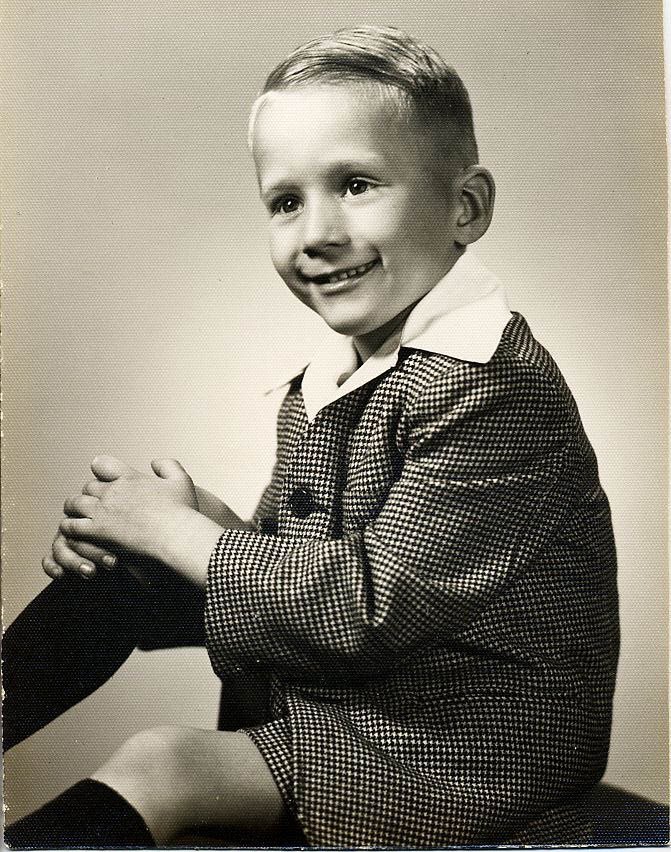

In Auburn, Nebraska (population 3,500), Louis Roland Magor was born May 16, 1945, the only child of John William Magor and Eleanor Niemann Magor. Although he shared a birthday with actor Henry Fonda and tenor Richard Tauber, he was boastful about having the same birthday as Liberace. Lou was originally taught piano by his mother, a piano teacher, and then studied for 12 years with Mrs. Inez Steinheider, with whom he maintained an affectionate correspondence until her death at age 94. Mrs. Steinheider discovered that Lou had perfect pitch, played by ear and had a singing voice. Magor recalled, “I wasn’t like other kids. I would practice all the time and show off when I got to her house. I did nothing else. I was Mister Piano. I played piano all the time. I would get up early in the morning and play. If we would be going on a family trip I would be thinking about piano, and thinking about how I would play a certain song and play various licks that I would have heard on television, that Liberace had played. So I was into it.”

Lou’s name was in the local papers before he was even eight years old, playing piano and organ, singing and even dancing. Magor told a Nebraska newspaper, “My mother and both grandmothers played the piano and I had played since I was five.” His father’s family had roots in Cornwall, England, and his mother’s family was of German ancestry. At home he conducted his father’s Fred Waring records and was inspired by the Fred Waring television show. Pretty soon Lou also became proficient on the electronic organ. Magor later told a reporter, “I was ten years old when Auburn decided to hold its first Miss Auburn Beauty Contest, and I was to provide the music for the parading contestants and also play a set while the judges selected the winner. My parents packed my organ, dressed me in my tux and we arrived at the high school auditorium. I’m sure that I was the focal point of the whole evening, simply because it was so bizarre to have a 10-year-old kid playing this pageant.” One of the piano pieces was Peter de Rose’s “Deep Purple.” “While the judges were making their decision I played my set. All I needed was the applause of 700 people. That was it. I had to entertain.” 700 was more than one-fifth the population of Auburn, Nebraska.

An outgoing student, at age 14 he was made regional representative for the Nebraska Boy Scout Explorers, where, as an Eagle Scout, he earned merit badges for swimming and cooking. At High School he was crowned King of the May. In 1960 he won a full scholarship to the annual All-State Fine Arts Institute at the University of Nebraska. He told a reporter “I performed Rhapsody in Blue for my fifth-grade classmates once. That was a thirty-page piece by heart.” Childhood influences included comedian Bob Newhart, Victor Borge, Mike Nichols and Elaine May. His retention of entire Newhart monologues contributed to his skill as a public speaker and became a permanent element of his future presentations. With equal ease he was able to dash off ditties by Tom Lehrer and Noel Coward. In 1979 Lou told the San Francisco Examiner that if he had all the money in the world, he would do exactly what he had been doing, “and,” he added, “I could afford it.”

Until he went to college he had not witnessed large scale classical music played by an orchestra. As a youth he considered Richard Rodgers (of Rodgers and Hammerstein) to be the world’s greatest composer. Years later he would be musical director for Mary Martin, who starred in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific and The Sound of Music.

CHICAGO

At Northwestern University he studied classical music and became aware of outstanding piano students. “When I realized there was all that talent on just that one campus, I decided then to give up becoming a professional pianist. I would go into choral directing. There weren’t as many of them around.” Professor John Paynter, a master teacher at Northwestern, was extremely valuable for Magor’s training as conductor of chorus as well as band. A former college roommate, Mark Hampton, noted. “At Northwestern University Lou had the ability to goof off, laugh and be crazy, and show up for everything and still get A’s. He had this infinite capacity for enjoying life.”

While earning Bachelor of Music Education and Master of Music degrees from Northwestern University, Magor taught choral music for five years in Chicago area high schools, including Avoca Junior High School and Niles North High School. Choral professor William Ballard also engaged Lou to arrange music for his various choral groups in Chicago. From 1964 to 1973 Lou became counselor and musical coach at Ojibwa Camp for Boys in Eagle River, Wisconsin. It was at Ojibwa that Lou learned how to transcribe and orchestrate music by listening to records. He helped to arrange and develop the annual shows performed by the camp members. After a 2013 reunion he rejoined the summer staff for another seven years.

SAN FRANCISCO

The San Francisco Symphony Chorus was created in 1973 by the symphony’s then-conductor, Seiji Ozawa. After recruiting 100 volunteer singers and 25 professionals, Ozawa went on a nationwide search for a choral director, and after a largely fruitless quest, asked Margaret Hillis, renowned conductor of the Chicago Symphony Chorus, for a recommendation.

Hillis suggested that Ozawa contact a former graduate student of hers, the 28-year-old Louis Magor, who was flown to San Francisco for the audition. Ozawa interviewed several conductors but was undecided until he received numerous letters from chorus members insisting on Magor for the job. It was while preparing the chorus for Seiji that Lou understood that imitation was “not a bad thing” and he studied the best conductors. Magor took pride in his selection of individual chorus members, the ages of whom ranged between 30 and 40 years. Their jobs covered the gamut from telephone pole lineman to corporate lawyer. Half of them were capable of teaching or conducting music on their own. Each chorus member devoted 30 to 40 hours a month to rehearsal.

Before the Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall was opened (September 1980), the San Francisco Symphony and the San Francisco Opera performed in the War Memorial Opera House, and chorus rehearsals were held at the Century Club on Franklin Street. A chorus member told a reporter that Lou was “brilliant. He manages to fire people up to sing well. He has such high standards. He communicates supreme self-confidence and that filters over on us.…He knows the sound he wants from us and he tells us clearly what we have to do to provide it. He’s great on diction. And there’s one more thing. He starts on time.” Another member said that he “literally knows every voice in the entire chorus.”

A critic wrote that the Symphony Chorus was like “one of the Ugly Duckling stories. It has gone from ragged gosling to luxurious grace in an amazingly short period of time.” Magor said, “In performing, I get to make the decisions. Music is done the way I think it should be done. I’m in control.…When I’m directing I’m practicing a craft. I have to be on top of everything. I can give myself over to the music, but I still must be within the framework of control. If I started thinking how beautiful this is, and slowed down even a little bit, then I’ve lost the whole pace of the thing.” During that same time period, Lou created the Louis Magor Singers, made up of 16 members selected from the Symphony Chorus.

In 1977 conductor Edo de Waart replaced Seiji Ozawa, who then took charge of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. When de Waart in 1982 asked Magor to resign effective the following year, the stunned chorus director instead chose to quit immediately. Magor knew it would be worse to remain for another year, preparing the chorus for someone who did not want to work with him. He was replaced by his mentor from Chicago, Margaret Hillis.

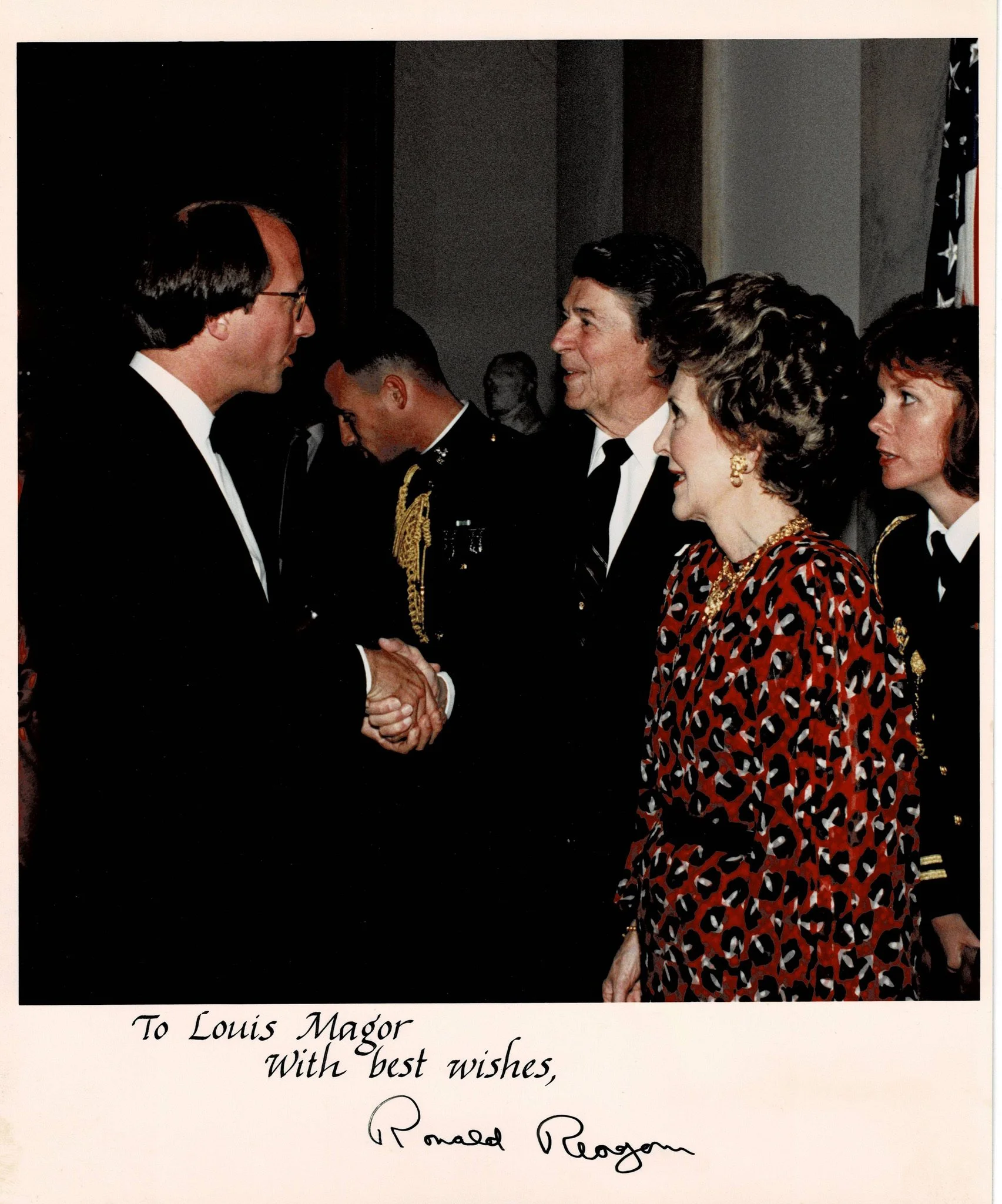

Soon after leaving the Symphony, Lou replaced William Ballard, who had been Magor’s undergraduate mentor at Northwestern University, as conductor of the prestigious San Francisco Boys Chorus, leading a national tour in 1985. That same year he conducted the Atlanta Symphony in a pops concert starring Mary Martin, who, with Carol Channing, participated in a full-scale benefit for the Boys Chorus during their San Francisco appearance in the ill-fated comedy Legends. Mary told a reporter “Happily we are going to be doing things together. [Lou] has such exhilarating ideas.” Martin and Magor met when he conducted the music for the all-star Mary Martin show at Davies Hall. Mary continued, “He has a great career ahead of him. He’s a fabulous musician, so quick and brilliant—he knows exactly what you’re trying to put over.” With Martin, Magor traveled and performed extensively, including with Marvin Hamlisch at the Reagan White House. Many of Lou’s recollections are found in David Kaufman’s Some Enchanted Evenings: The Glittering Life and Times of Mary Martin (St. Martin’s Press, 2016).

In 1982, to show his appreciation to his hometown, Magor and an entourage flew to Auburn, Nebraska, to conduct a massive “Festival of Song,” a 75-minute concert of at least a dozen choirs from all over Nebraska. The 150 voices included about 30 Auburn sixth graders. Also on the program was a women’s handbell choir from North Platte.

During his years in San Francisco he inaugurated the Sing It Yourself Messiah, a Christmastime musical event that raised thousands of dollars for the San Francisco Conservatory of Music and became a much beloved tradition. The joyous annual event was televised live by KQED Public Broadcasting Service to millions of viewers. While in San Francisco Mr. Magor was also the Conductor of the Bohemian Club Chorus, Schola Cantorum, San Francisco Conservatory of Music, San Francisco State College Band, and the Louis Magor Singers. Suzie Argenti, one of his selected Louis Magor Singers, recalled, “Integrating many musical styles he not only pleased but educated audiences.”

SEATTLE

Lou moved to West Seattle in 1990 and it turned out to be his longest residency in any city. Whitney Tjerandsen, a former member of the S.F. Symphony Chorus, had moved to Seattle in 1977 and sang with the Seattle Symphony Chorus. In 1990 Seattle Symphony needed a new choral conductor, and Tjerandsen recommend Lou Magor, who traveled to Seattle for an interview. Although Magor was overlooked by the Seattle Symphony, he had an interview with the Seattle Bach Choir that led to a successful position for eleven years. Tjerandsen, who founded Tilden School in 1985, hired Magor as music teacher to students ranging from kindergarten to 5th grade, a job that lasted 31 years.

For several years Magor appeared on Seattle’s popular Sandy Bradley’s Potluck, broadcast on National Public Radio every Saturday morning in front of a live studio audience, and considered to be Seattle’s version of Prairie Home Companion. He was conductor for the Seattle Bach Choir and the West Seattle Children’s Chorus and Music Director at Wallingford United Methodist Church. Magor’s San Francisco friend Bob Stabile (known professionally as Hokum W. Jeebs) moved to Seattle after Magor and they founded Hokum Hall in the rustic, former Olympic Heights Social Hall at 3904 35th Avenue S.W. Following a dissolution, the venue changed its name to Kenyon Hall, a nonprofit performance space with a grand piano and a 1929 Wurlitzer theatre organ. Under Magor’s direction magicians, organists, singers, musicians and comedians filled the Kenyon Hall calendar. Magor took pride in booking performers from out of state, some from as far as New York City. This unique roster included Dave Frischberg, Carole J. Bufford, Arthur Migliazza, Robin Sutherland, Ronny Cox, Roy Zimmerman, Eddie Vedder, Casey MacGill, organists Dennis James and Bob Mitchell, Jay Leonhart, Ray Skjelbred, Peter Mintun, and Rebecca Kilgore.

As accompanist to Seattle’s Total Experience Gospel Choir (founded in 1973 and directed by Rev. Patrinell Wright), Magor traveled around the world and across the U.S. in concerts that raised money for victims of Hurricane Katrina. For 2-1/2 months in 2013 he toured with Ann and Nancy Wilson as chorus director for the legendary rock band Heart. He told an interviewer, “My job was to conduct a local gospel choir in each of the cities for the last three minutes of Stairway to Heaven. It came out of the tribute at the Kennedy Center tribute to Led Zeppelin. Ann and Nancy sang, in a very popular YouTube clip now, Stairway to Heaven. At the last moment they revealed the gospel choir and they joined. So they decided, ‘Hey, that worked. Let’s do it on tour.’ They did it with Jason Bonham, who was the son of Jon Bonham, the drummer for Led Zeppelin, who had passed away many years earlier. So it was the Jason Bonham Band and Heart, two bands touring around the country, playing Ravinia and other outdoor venues.”

Although the COVID-19 pandemic ended live performances in 2020, Kenyon Hall produced virtual concerts, and Magor mastered the art of Zoom teaching. A highly regarded educator, Magor taught Kindermusik Kids Music Classes (birth to age seven) and K-5 students at Tilden School.

Lou’s world revolved around live music, a term that would have puzzled the Victorians. He loathed background music and used the radio solely for National Public Radio. His home was devoid of recorded music. Cassette tapes and LPs sat in boxes, un-played.

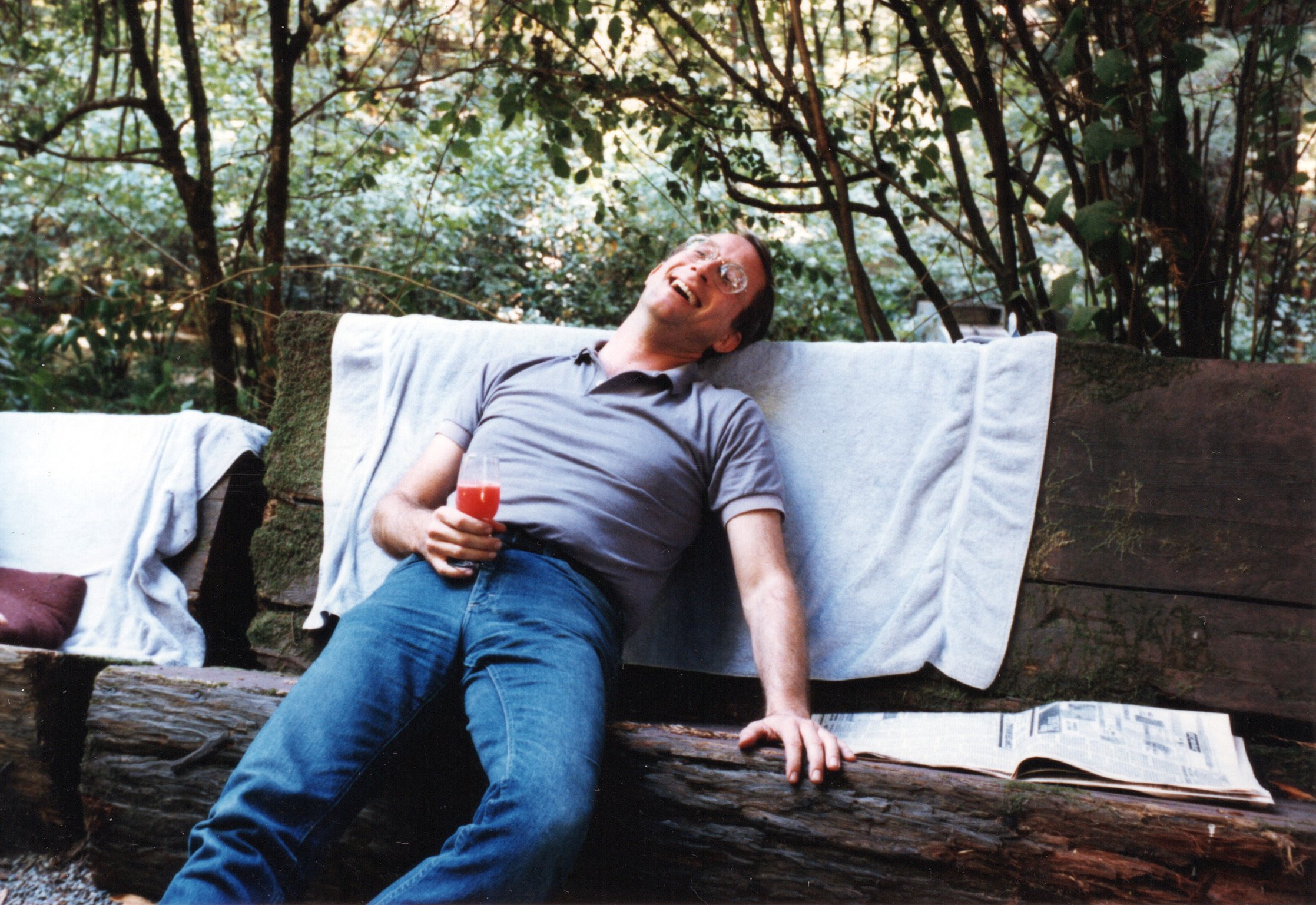

Supremely self-confident, Magor enjoyed his celebrity. At several restaurants he could sit in a chair close to his framed photo on the wall. His Handel’s Messiah class was formally called Learn It With Lou. The local bartenders knew how to make the perfect “Magor-tini.” During the pandemic, the outdoor lanai or patio of a restaurant became the “Lou-nai.”

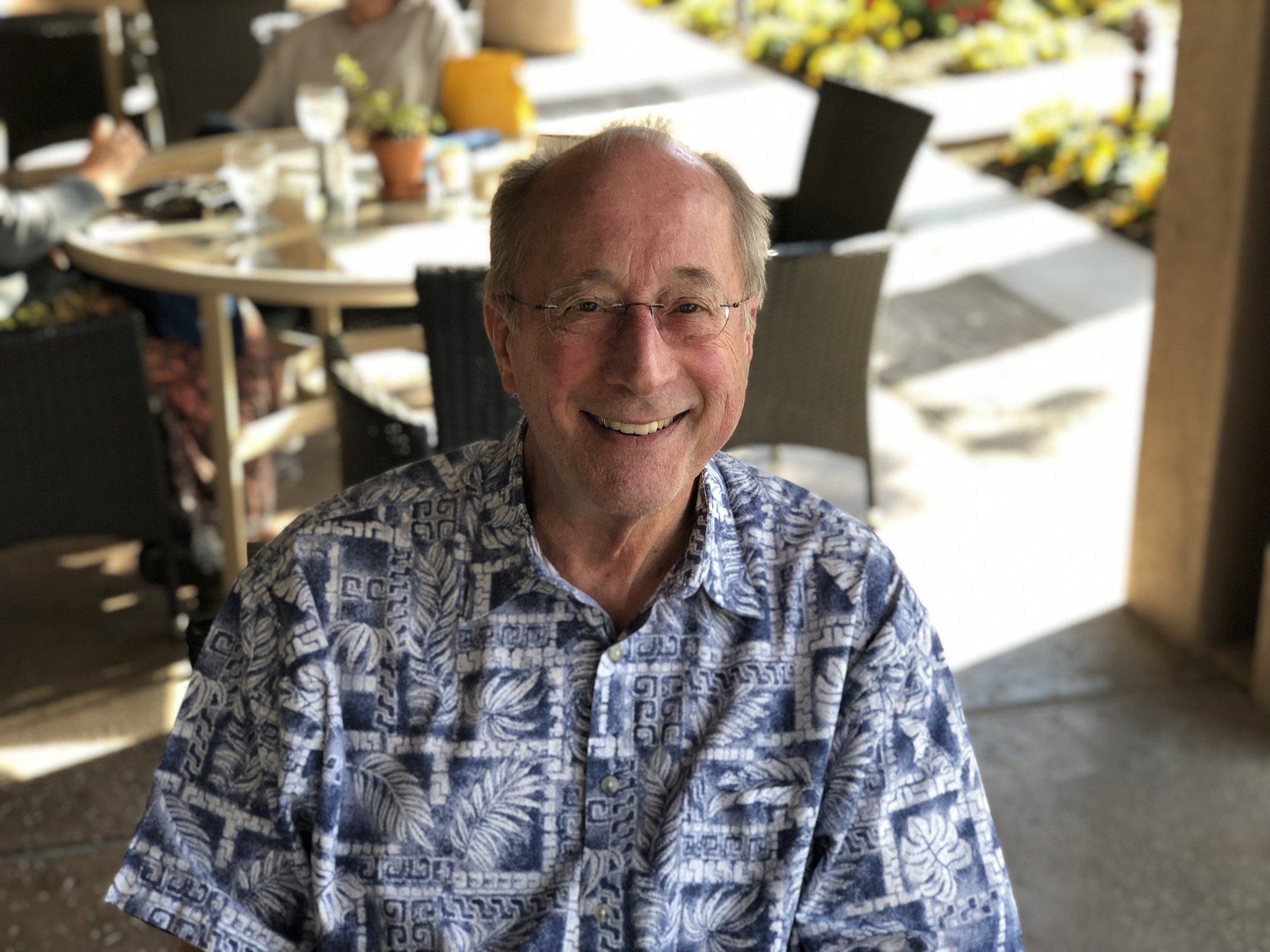

At the time of his death, Magor’s virtual classes were highly successful and gratifying to students and parents alike. He is survived by nine cousins from the Magor and Niemann families, located in various states in the U.S.

“Music is always something I can do better than others. But also,” Lou once said, “music is one of those things that, thank God, can’t be described in words. Without it I’m lost. With it I’m happy. I guess what it means to my life is that it IS my life.”