Elements of Craft: The Semi-Philosophical Musings of an Architect-Musician

By Gustavo Alonso López

As an architect-musician on a strange and uncertain path, I have learned some useful lessons about craft from my respective disciplines. Craft is a familiar word, but what exactly is it? Is it technique? Is it mastery of an instrument or medium? Does it depend on something physical? Do audiences play a role in defining it? How specific or universal is it? I see craft as a form of artistry specific to and independent of creative discipline. It goes beyond technique, materials, and precision into more elusive realms such as emotion, imagination, communication, and meaning.

According to standard dictionaries, craft is defined as both a noun and a verb: an art, trade, or occupation requiring special skill, and to make or produce with care, skill, or ingenuity. In architecture, this includes actions like drawing and model-building. In music, it includes playing an instrument, singing, composing, recording, etc. In both fields, however, craft means much more than technique, skill, or know-how. The distinction is necessary because discussions of craft often overemphasize technique and neglect its other components.

Conceiving an architectural design requires knowledge of two and three-dimensional representation, geometry, space, structure, and materiality, but also of culture, society, aesthetics, politics, history, and more. Similarly, playing a musical instrument demands control of certain techniques and basic music theory, but also the development of an instinctive understanding of genre, performance practice, style, feeling, and audience expectations. All of these are part of a larger definition of craft. Artists are more than technicians. There are many mediums, techniques, and skills in use, but artists share a deeper sense of craft from which broad principles can be extracted. My concept of craft consists of, but is not limited to, the following elements: technique/skill, repertoire, exploration, strategy, coherence, revelation, and purpose.

Image by Mallory MacDonald

Technique

Technique is a specialized physical action, the use of a tool, or a collection of procedures. Importantly, it is also the manner in which these are employed. An artist uses technique to acquire and hone a skill. Holding and swinging a hammer correctly are techniques. Hitting the nail on the head consistently and accurately is a skill. Technique is fundamental and necessary, but it is only part of the equation. A baseball player’s 110 mile/hour fastball is not worth much if that fastball isn’t thrown at the right location at the right time. Technique is the vehicle that moves one from point A to point B. Although artists must continually advance their technique, technique is not the objective itself. It is there to help overcome creative obstacles. If a musician imagines a sound, but does not have the right technique, the sound cannot be produced.

Acquiring new techniques gives an artist new expressive possibilities, and the search for expression leads to the discovery of new techniques. It works in a continuous feedback loop. Not all disciplines require the same level of technique. Some techniques require precision or a proper sequence of actions; they are procedural, but not physically challenging. Others make huge physical demands of the body. For the more physical disciplines, such as being a concert instrumentalist, technique also serves another critical role: the prevention of injury. In all cases, however, good technique does not necessarily lead to good art. What’s necessary is to use one’s technique in service of the artistic work at hand. It is what carries the artist through the creative journey.

Repertoire

Repertoire is the foundation of an art form’s tradition. Artists learn the history of their discipline through the rigorous study of repertoire. The weight of history holds certain artists back. Others build on it and evolve. And of course, there are also those who ignore or rebel against tradition completely. Regardless of approach, tradition’s influence cannot be avoided; it must be reckoned with one way or another.

One key ingredient to the success of flamenco dancer Pastora Galván, for example, is her ability to simultaneously incorporate ideas past, present, and future into her work. She is firmly grounded in the traditions of her discipline, but heavily influenced by new concepts and ideas, and especially by her older brother Israel, one of the most radical and avant garde of all flamenco dancers. The knowledge of her art form’s history is not an obstruction, but a foundation.

In a musical context, the concept of repertoire is commonplace. In flamenco, the music to which I dedicate myself, there are specific compositions, standard structural forms (palos), falsetas, accompaniment recursos, rhythmic cycles, marking patterns, and harmonic and melodic passages, just to name a few. In architecture, my other discipline, the term repertoire is uncommon, but is closely related to the concept of typology.

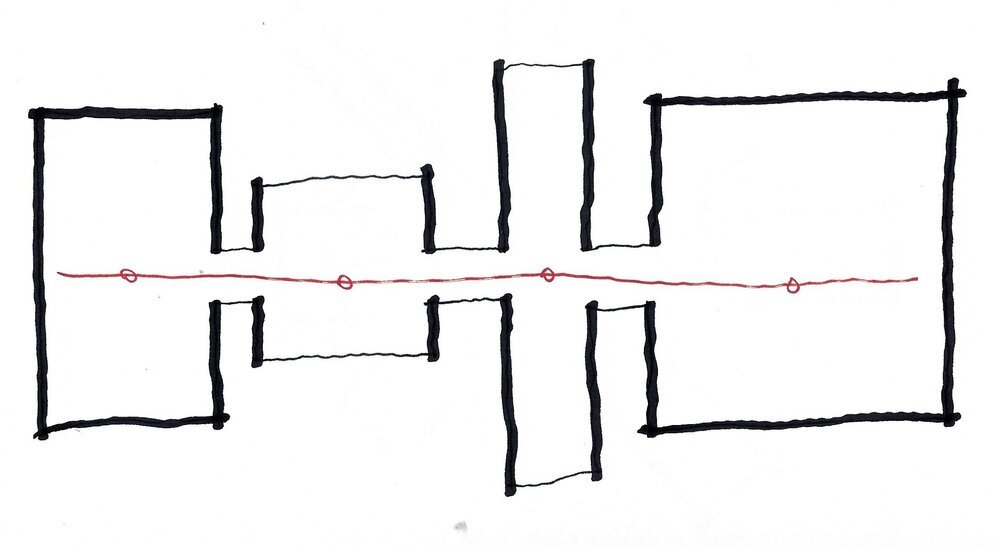

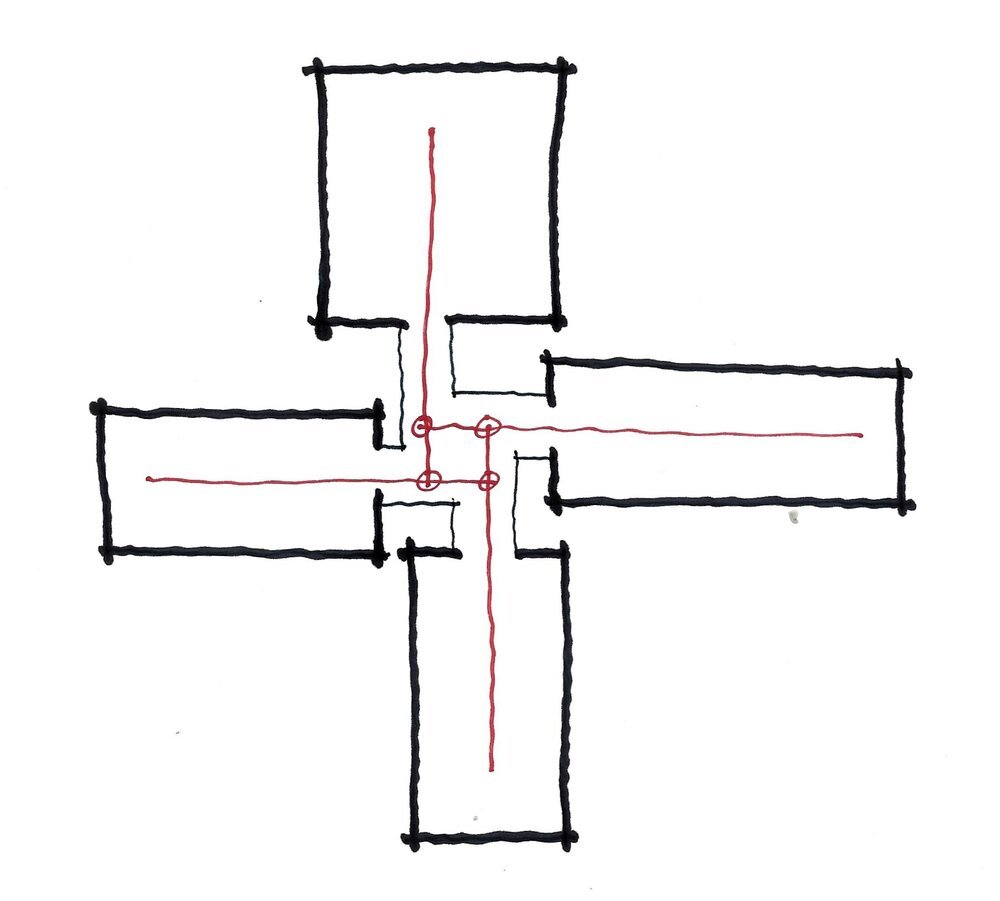

Typology is the study of types, and their systematic classification and categorization. In all but the most radical architectural schools, typological study is an essential part of an architect’s education. There are compositional typologies—axial plans, radial plans, and pinwheel plans, for example. There are functional typologies—hospitals, libraries, schools, and houses. There are material typologies—brick buildings, concrete buildings, and wood buildings. By actively studying and analyzing building types, an architect gradually builds a design repertoire. Regardless of whether it is architecture, music, or any other discipline, studying repertoire is critical in the development of craft. It explains what’s come before and opens doors to new, fertile territory.

Exploration

The creative act demands constant exploration. The act of searching itself helps define craft. If a technician displays virtuosity with playing the cello, laying brick, or painting in oil, an artist has something more. Artistic craft involves expertise in the search for meaning. Artists pursue new and authentic interpretations of emotion, truth, ideas, and messages. They aspire to understand the world more deeply, to define and capture their perception of beauty, and to share that understanding with others.

In the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the New York Philharmonic commissioned composer John Adams to create a piece for the first anniversary of the event. On the Transmigration of Souls is an orchestral work dedicated to memory, loss, and sorrow. In interviews, Adams cites the difficulty he had in determining how to approach this music. He wanted to avoid politics and daily news headlines, but couldn’t see how he could possibly express the subject’s magnitude. He was overwhelmed and questioned the wisdom of accepting the commission. Eventually, through methodical and diligent research, he found small handwritten notes published in the newspaper. They were simple, direct, messages about or to the deceased, written by their loved ones. Steadily, his piece took shape by weaving spoken fragments of these messages into an orchestral environment layered with musical symbolism. The result was moving, deeply human, and apolitical music.

Adams is an accomplished composer, yet even someone of his stature found himself empty-handed and with no clear direction at the outset. The search that eventually led to the genesis of this piece was itself part of his craft as a composer. Artists share something with archaeologists in this sense. Archaeologists embark on digs systematically. Once they find something, they are meticulous in how they proceed to uncover it, advancing with care and focus as they unearth their find. There’s a process to their searching that requires planning, patience, and careful execution. Adams’s process was similar, and it shows that the need to explore is persistent and answers must be sought anew with each project.

Making art means searching for something artists don’t already have and may never find. Whether it’s a budding amateur, a student, or a figure like Pastora Galván, John Adams, architect Louis Kahn, or guitarist Paco de Lucía, making art involves an existential search for the most sincere interpretation, expression, feeling, or message one can create in a given moment.

Strategy

Craft also requires strategy. Whether consciously or not, successful artists make choices and they plan. The moment a painter or photographer decides how to crop an image, that’s strategy. When an architect locates a building on site or chooses which materials to use, strategy is at play. When a musician starts a new composition in a given key or time signature, those are strategic parameters.

Strategic decisions set a range of actions into motion, which then influence subsequent challenges and issues. If a composer begins in a certain key, a decision about whether or not to remain in that key or modulate to another one will have to be made. When an architect chooses a given material, decisions regarding, color, texture, thickness, luster, shape, transparency, cost, and installation must follow.

When designing the Kimbell Art Museum, for example, architect Louis Kahn made many clear strategic decisions. One was to place all galleries on a single level so each had a consistent relationship with the roof, which is the project’s key feature. Consequently, each gallery had equal access to the natural light entering through the roof. This is essential, because few buildings in the history of architecture harness natural light with the virtuosity of the Kimbell, and each artwork directly benefits from this.

“Passing through the glass doors we arrive in the entry gallery, one of the most beautiful spaces ever built. Without exception, all who enter first lift their eyes to the ceiling above, which, though having the same profile as the porticos outside, is in every other way transformed. Where the porticos are continuous curves, the interior vaults are split at their center by the skylight and reflector; and where the porticos are dark against the bright sky above, the interior vaults glow with the most astonishing, ethereal, silver-colored light.” (Robert McCarter, Louis I Kahn, 2005)

Kahn’s decision was just one in a set of important variables that established his overall approach. Together, these variables work to build expectations and context, to manage execution, anticipation, ambiguity, and tension, and to control movement, procession, and sequencing. They define parameters. Without parameters, one lacks focus and intention; there’s nothing to guide the creative process. Parameters direct actions and set the criteria by which a work will be perceived, understood, and evaluated. Strategy is the process of working within and using these parameters.

Image by Gustavo Alonso López

Coherence

Coherence is a natural result of a well-conceived strategy. If presented with a coherent concept, the audience has something to which it can connect. Without coherence, art risks failure because the message may not be received or understood. Without structural coherence, a building cannot resist gravitational forces. The same thing occurs in language. If two people don’t share a common grammar or vocabulary, they simply cannot understand each other. However, this is not to say that the message or structure must be overt or simplistic.

Just because something is difficult to understand does not mean it is incoherent or unfocused. Much in jazz, flamenco, and contemporary art can seem chaotic, fragmented, and unorganized, but it is not always so. Internal logic and structure are there, although they might be imperceptible on the surface. However, if well-designed, this logic often works on a subliminal level, allowing for reception of the message.

Flamenco rhythms are highly textured and complex, both in the metrical sense and in terms of phrasing. They are polyrhythmic, syncopated, and asymmetrical. While the inner pulse is often disguised and the sense of time is malleable, these occur within an established framework. The structure is open and flexible, not closed or fixed. As a general rule, the more hidden or unconventional the underlying structure, the more discipline a work needs. A deep understanding of underlying structural connections, be they geometric, tonal, material, or temporal, creates coherence. If art is coherent, the artist is generally in control of their craft.

Revelation

Revelation, or surprise, captures the audience’s imagination and curiosity. If genuinely surprised, people become invested in the experience. If they’re invested, they’re open to receiving artistic messages. Surprise is sometimes the result of breaking the rules, so to speak, of working outside the above-mentioned strategic parameters.

Finding the right balance here is challenging. Surprise comes in many forms and need not always be dramatic. It can be radical, abrupt, and uncomfortable, like the contemporary flamenco dancing of Rocio Molina. It can also be gradual, subtle, and meditative, like the minimalist music of Philip Glass. Surprise is not necessarily innovative, original, or revolutionary. It has more to do with controlling timing.

It is helpful to think about how the great flamenco guitarist Paco de Lucia’s music evolved over the course of his career. Beginning as a child accompanying his older brother, Paco was immersed in the traditions of singing and dance accompaniment, which is the essential component of a flamenco guitarist’s training. Later, he moved on to work with some of flamenco’s greatest artists. Gradually, he built his own ensemble and started working more as a solo artist performing original music. He incorporated influences from jazz, bossa nova, and classical music into his playing in ways that were both counterintuitive and different, but firmly grounded by his flamenco roots. In doing this, he revealed how diverse sounds could coexist within and reinforce flamenco’s identity.

Paco’s innovations were often strange and different, but unmistakably flamenco. What was once harmonically static evolved to rival jazz and classical music in harmonic complexity. By bringing this into what was already a rhythmically-advanced music, the possibilities for flamenco expanded to what they are today. His commitment to exploration opened new doors and has allowed later generations of flamenco guitarists to develop and extend these revelatory ideas. Artists like Paco de Lucia understand how to break rules and conventions effectively, to draw audiences in, and transport them to unexpected places.

Purpose

Arguably, the most important element of artistic craft is purpose. It comes in many forms and means different things to different people. However, there is a reason why something is done.

An example from outside the arts can help illustrate. In the world of motorcycle racing, the objective is clear. Engineers and mechanics design and tune the machines. Riders train to be physically and psychologically fit; they learn proper riding techniques; they study the track, riding data, and weather conditions; they study their opponents; they test the feel of the tires. This is done with exactly one purpose in mind, to cross the finish line first.

The concept of purpose is more difficult to articulate in the realm of art, because the goals are not as easy to identify. However, purpose exists. It may be to honor loved ones, protest injustice, memorialize an event, express a feeling, exploit the possibilities of a material, or satisfy a personal obsession. Purpose is not synonymous with meaning. An artwork can have purpose without specifically meaning anything. An artist can create purposeful work without any deliberate intention to embed meaning. Meaning is different altogether, and is often out of the artist’s control. Audiences create their own meaning through the filters of their individual worldviews, personalities, and life experiences. History, events, and the passage of time also affect how meaning evolves and changes.

While the point is debatable, I suggest that one of art’s purposes is to transcend the specific and enter the realm of the universal. I don’t see universality as absolute or black and white; I see it more as a continuum or a spectrum. When a piece approaches a sense of universality, it approaches timelessness. It’s no longer strictly limited by style, time, or culture. It reaches deeper and further. Great art endures because it touches audiences across cultures, social classes, and disciplines. Our shared humanity, collective memories, primal desires, intellectual ambitions, and utopian ideals are embedded within our art. This is why the music of Ravi Shankar, Nina Simone, Frederick Chopin, and Niño Ricardo remains alive, or why architectural pilgrims traverse the globe to places like Granada’s Alhambra palace, Ronchamp’s Notre-Dame de Haut, Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia, or Washington DC’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

Image by Gustavo Alonso López

* * *

Many personal and professional experiences have shaped my concept of craft. The specific formula or combination of elements that make art successful is complex and difficult to predict. To reiterate an earlier point, technique often takes on too important a role.

I have seen many young architects and musicians struggle with this; they are often obsessed with technique. This is understandable. Architecture and flamenco are overwhelmingly technical, so it is easy to get lost and exhausted in the pursuit of technique. Routinely, I have to step back and ask myself, “What am I doing here? Why is this important? What am I trying to say?” I have to constantly remind myself that having great technique will not make me an artist. There’s much more to it, and if I spend too much time practicing technique, the rest of my craft gets neglected. The remaining elements — repertoire, exploration, strategy, coherence, revelation, and purpose — also require dedicated study and practice.

Artists must also accept their own vulnerability, because not every creative journey is successful. One works with the constant risk of failure and disappointment. In the world of performing arts, the stakes are high because the risk of public failure is quite real. A lot can go wrong when you are alone on stage with hundreds of people in the auditorium! If you aspire to be an artist, place the elements into an equilibrium that works for you and commit yourself holistically. This will help your art connect to others, reflect yourself and your world, and will help make it last. You will be well on your way towards making art of real value and meaning.

Gustavo Alonso López is a flamenco guitarist and registered architect based in Austin. His music is grounded in traditional flamenco and incorporates elements of jazz, classical, and world music. He has one full-length studio recording titled Punto Lejano (A Distant Point), and was awarded a Fulbright performing arts fellowship in 2017 to advance his musical craft in Sevilla, Spain. As an architect, he has over a decade of professional experience, working at different scales across multiple sectors of the building industry. He is a member of Common Tone Arts’s board of directors.

For more information please visit Gustavo’s artist site at MusicaLopez.com and his flamenco blog at Palabrasflamencas.com.

Thank you to Brian Chin for inviting me to collaborate on this project, and to Chris Stover and Alessandra Zielinski for their thoughtful feedback and editing.